I've been a board game creator for a while, but I'm newer to fatherhood, with only about three years under my belt. Just before my son turned two, he expressed interest in the games he saw me designing. So I started to teach them to him, and now we play games most days, which is a dream for a dad that's also a board game creator.

These regular board game interactions with my son have had unexpected and wonderful consequences. For example, he's learned basic math, with hardly any instruction, as a byproduct of the numbers in our games.

He's learned lots of other things too and all more quickly and naturally than I expected. When we're playing games, there are no schedules, lessons or requirements–just the joy of learning through play, which he daily asks me to join him in. This seems to be a key reason he's learning so fast–when intrinsic motivation is combined with fun, it seems to create startling results.

But my son's not the only one who's learned. I have too. I try out all sorts of games with him, and I watch. I watch what he likes, what he dislikes, what he does and doesn't understands, and the way some ideas ferment in his head and others slide right out.

All this time spent playing or watching my kid with games has taught me two new things about game design.

1). The World is a Database

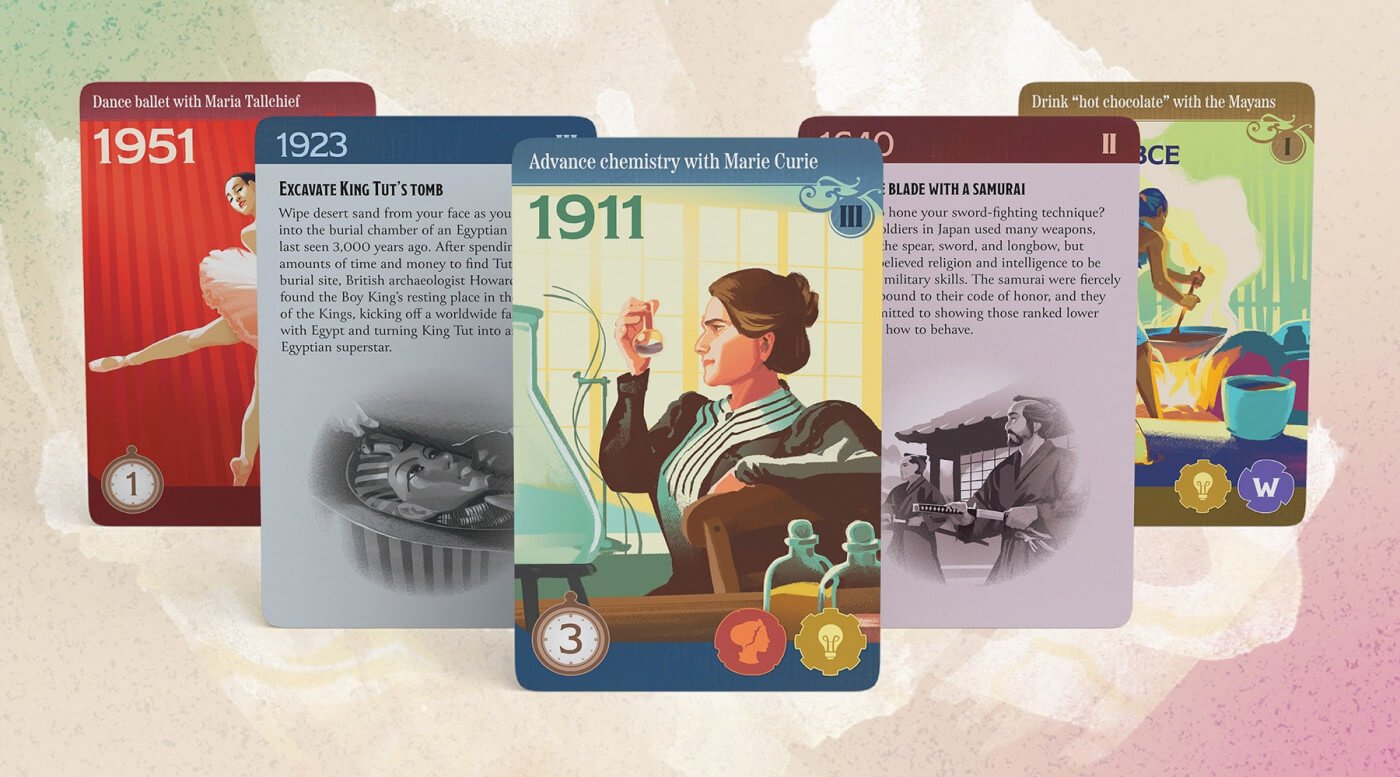

Kids can't hold things in short term memory for very long. So when my kid plays a game, he needs to somehow overcome the fact that he can't remember anything. Watching how he does this has made me realize something: we use our visual environment to store data. If some idea or rule is embodied as a picture or an object in a game, he can always reference it with his eyes when he invariably forgets and then remembers the concept. Ideas or rules without concrete visual representations will usually be lost to him.

But this is true of everyone! We all have a pretty low ceiling on what we can hold in short term memory (roughly 7 things, even for adults), and so we could all use an external database. So now I think about how the visual interfaces of the games I build store data.

2). I've Changed the Way I Look at Innate Universal Pleasures vs. Specific Acquired Pleasures

Finding out what my son likes and dislikes has forced me to contend with the idea that a few pleasures are innate and many more are acquired through experience. I've noticed that, not only my son, but every other kid who plays games at our house, ALL take immediate pleasure in the following two things:

- Throwing physical objects

- Acquiring physical objects

I could write a long essay about each of these pleasures, but I'll keep it high level. The reason this has become important to me is that there is HUGE variance in how people experience games, and this is one of the biggest obstacles to making games which are good products–it's hard to make them universal enough.

It's easy to make a game that 10% of players think is awesome. But that's a bad product. If 9 out of 10 people playing a game don't take much pleasure in it, you won't be very happy that you bought it. It's really easy for a game designer to inadvertently make things like this because, in virtue of being a person, they enjoy specific things about games that others don't. So I can make something that I, the designer, absolutely love, but then later find out I'm in some 10% category. This is actually the norm, and the reason, in my opinion, that designers shouldn't regard their own pleasure in their creations as any kind of predictive signal.

All of this has led me on a search for the universal. And it's easier to see the universal in the very young. You may be surprised to learn Exploding Kittens ISN'T the best-selling game of the company that makes it. Another game, called Throw Throw Burrito, is. That's a game where players throw foam burritos at each other. I suspect the reason it's popular is because it taps into the universal pleasure of throwing. Likewise, we have a game called Coconuts, which seems to be the most universal game we make, in the sense that more kinds of people can enjoy it than any of other of our games. It's built around using little monkey launchers to send coconuts into the air in an attempt to land them in cups.

Anyway, I'm grateful for the time I spend playing board games with my son, and the insight I gain from it is an incredible added bonus. It's made me think much more carefully about the universality of the pleasures I want to conjure in the games I design, and I think it's made me a better designer. Well, at least I hope so.

Learn more about getting kids into board gaming with this article, which explains how to keep it a positive experience.