Welcome to this week's behind-the-scenes post.

A Communication Dilemma for Board Games

One of the biggest challenges of making things for people is communicating why those things might be of use to anyone.

When you sell a problem-solving product, the thing to convey is how the product solves the problem. Obviously.

While it can be said board games solve problems, they're fundamentally entertainment. Their main purpose is to create experiences.

How to communicate what those experiences are like?

All entertainment products have this problem in one way or another, and they try to solve it in different ways:

Movies have it easy-ish. They communicate with trailers, which are like tiny versions of the movies themselves.

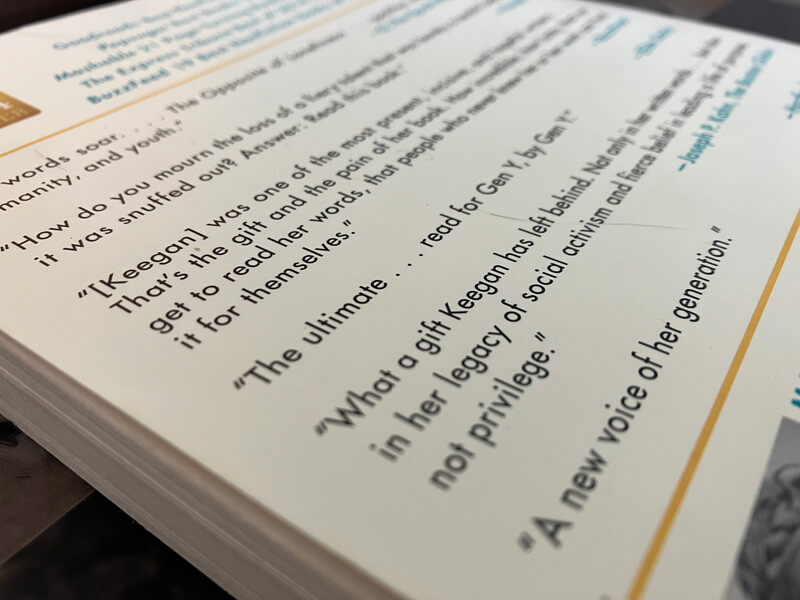

Books have it harder. The experience is more in the mind. You could make a trailer from text snippets, but I doubt it would work: not enough context.

I suspect that’s why book publishers rely on testimonials. In the absence of a direct way to show the experience, publishers use descriptions of others’ experiences.

Strategy board games are more like books than movies

We can (and do) make trailers showing the game on the table and people playing, but that doesn't communicate well what it's like to BE those people. The experience is more internal, like a book.

Video play-throughs are a little better but they demand such a time- and focus-commitment, they fail to be helpful to many.

This is my struggle as I prepare to launch a game. Options I’m considering:

Improved Testimonials. Like book publishers, board game publishers already rely on testimonials. I wonder if we can do a better job.

I can think of three ways to try to improve testimonials:

- Share unsolicited testimonials (found instead of asked-for). I think they're more authentic and representative, and for that reason we're already doing this.

- Share more testimonials. It's easier to understand a game through the lens of many perspectives instead of just one. Marketing books will recommend using no more than three testimonials in any piece of communication, but if you really want to help someone understand if a game is for them, surely that's not enough.

- Share negative testimonials in addition to positive ones. This may sound counterintuitive but I think this may be the most important. There is no board game that everyone likes. To really help someone understand if a game is for them, we should share the perspectives of those who don't like them. One potential problem with this is that it is surprisingly hard to get negative testimonials before a game is published. Those who don't like the game either tend to stay silent, or they've avoided being playtesters in the first place.

There was a reviewer on Board Game Geek who used to write reviews through the lens of the comments left by people who rated the game, negative and positive, and I thought they were among the most helpful reviews I'd ever read. Here’s a collection those reviews.

Doing this effectively is easier now than then, because AI has gotten really good at summarizing text.

This kind of practice could be amended by clear descriptions not only of who a game is for, but who it's NOT for.

I believe doing so is good for both publisher and customer:

- Good for customers because it makes it less likely a customer will waste money on something they won't enjoy.

- Good for the publisher because self-criticism builds credibility, and also limits the number of negative online reviews from people who bought the wrong thing.

Make extensive text and video about what we're trying to accomplish and how. This could be supplemented with podcast interviews where we can talk about that. The challenge would be making it compelling enough. This is like the other most-common communication practice in the book industry: book tours.

Slightly unorthodox idea: we could have playtesters describe what each turn feels like immediately after taking it. After we've collected a set of such "turn diaries", we could use them to better understand what kind of language we could use to more accurately convey what a game is like.

Another unorthodox idea: hold a contest where players can submit descriptions of what their experiences are like, and we use this to generate a richer set of descriptions.

Would love to read you own suggestions if you have any,

Nick